Chapter I

The Little Wren in Winter

The little wren — who would have thought.

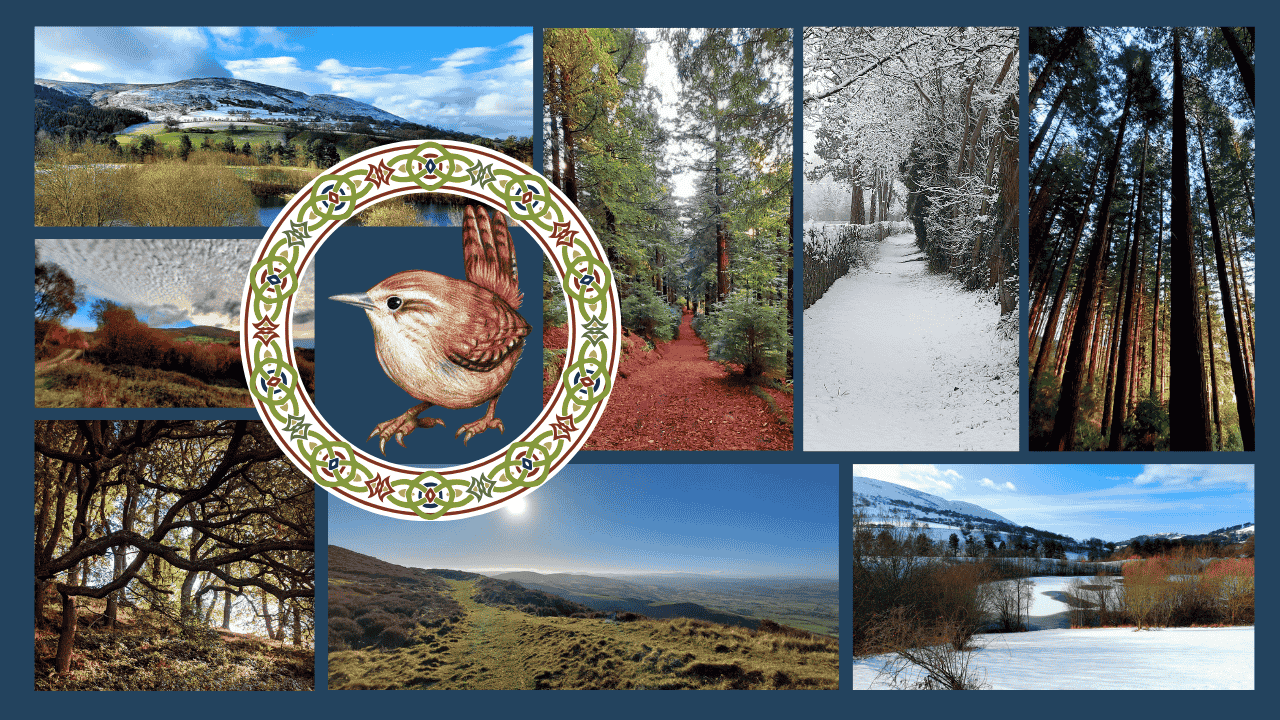

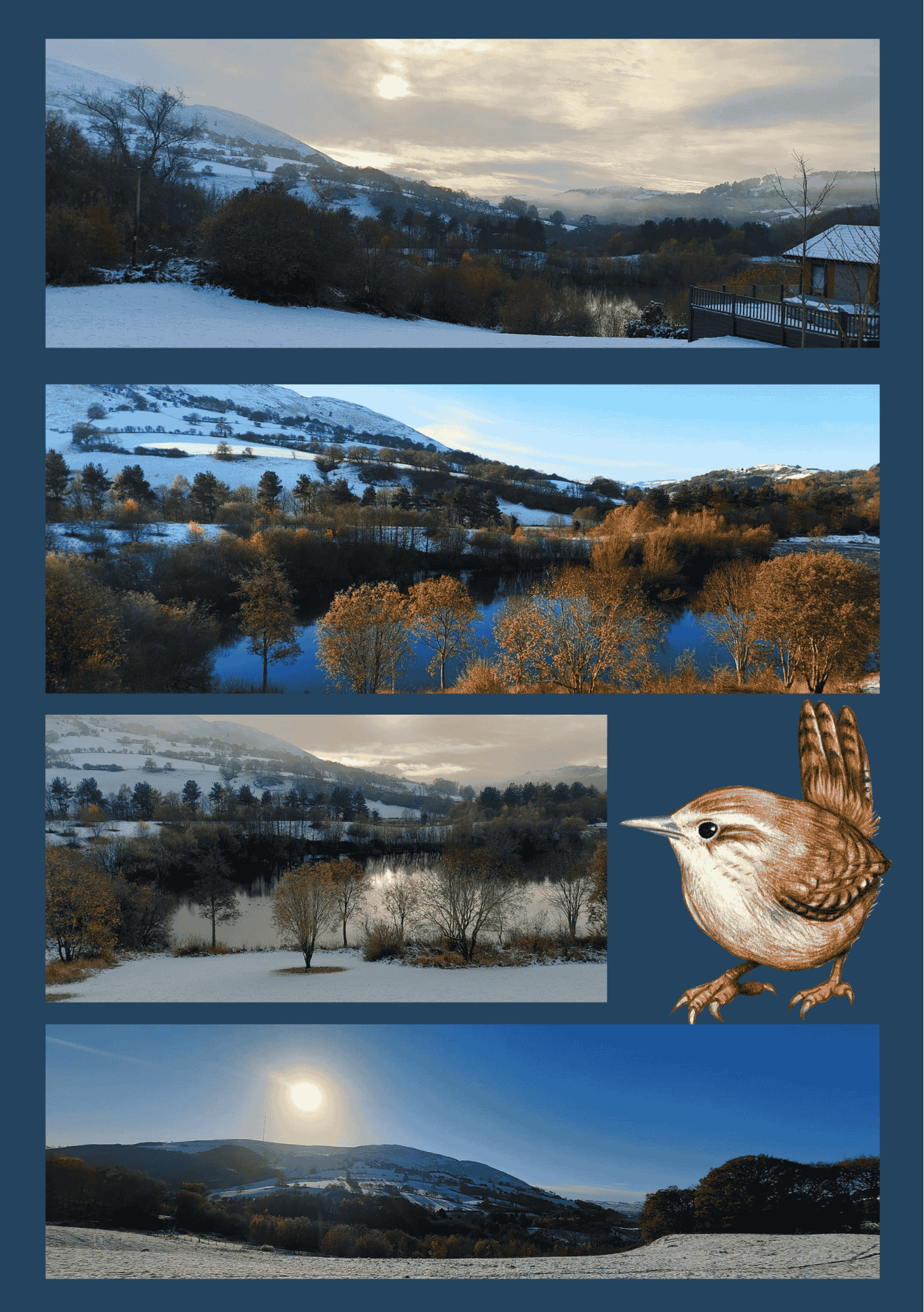

At Maes Mynan Park, winter arrives softly. The hills hold their shape beneath pale skies, the lakes grow still, and the park settles into a quieter rhythm. Trees stand bare and honest, hedgerows thin, and the land reveals itself without distraction.

And yet, close to the ground, there is movement.

A family of wrens lives just outside the park office, flitting between low shrubs and sheltered hedges. They are quick, almost secretive — a flicker of life easily missed if you’re not paying attention. But once seen, they become part of the landscape’s winter character: resilient, alert, quietly enduring.

In the deepest part of the year, when much seems dormant, the wren remains present. It does not dominate the scene. It belongs to it.

Chapter II

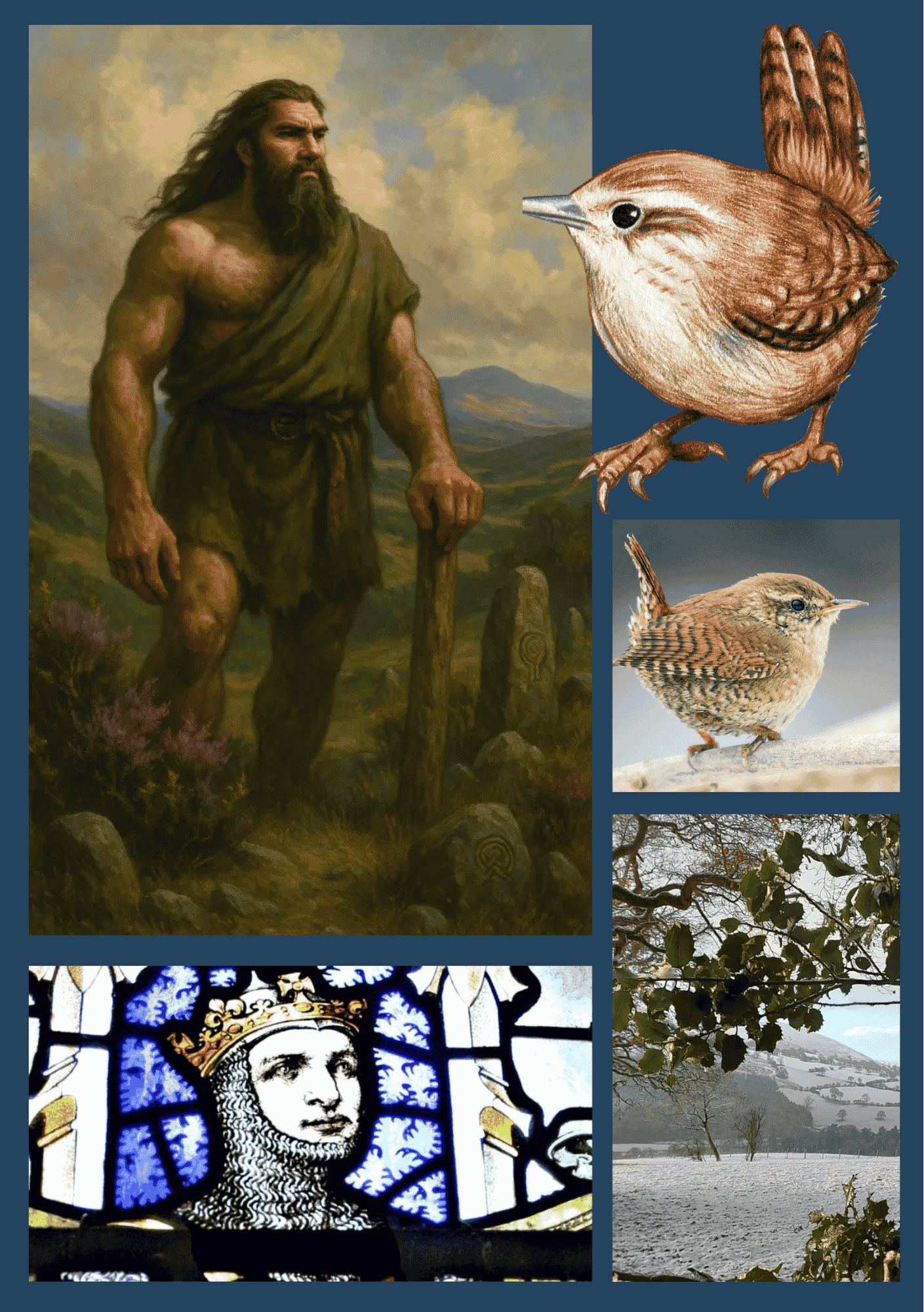

The Druid of Birds

Long before calendars divided the year and before Christmas carried its modern meaning, the people of this land marked time through nature.

In Celtic tradition, the wren was known as drui-en — the “druid of birds.” Its song, sharp and surprisingly strong for such a small creature, was believed to carry knowledge. Not noise, but meaning. Not volume, but insight.

Druids did not seek wisdom through grand gestures. They listened. They observed patterns — the movement of animals, the turning of seasons, the way light shifted across the land. The wren, living close to the earth and hidden within hedgerows and woodland edges, embodied that quiet attentiveness.

Here in North Wales, where ancient hills and valleys have always shaped human life, such beliefs feel close to the surface. This is a landscape where stories were carried by voice rather than page, where understanding came from watching and waiting.

The wren did not rule by force. It endured by awareness.

Chapter III

Land Before Lines on a Map

Before there were borders, before towns and roads had names, this land already knew itself.

The slopes above Maes Mynan, the valleys beyond, the routes wildlife follows through hedges and woodland — these patterns long predate ownership or administration. Wrens lived here then as they do now, threading their way through cover, indifferent to the passing of centuries.

Nature does not recognise eras in the way people do. It responds instead to light, shelter, food and season. The wren survives not because it is powerful, but because it understands its place.

Winter reveals this truth clearly. Stripped of leaves and colour, the land shows its bones — and reminds us that continuity is often found in the smallest things.

Chapter IV

Roads, Stones and Empire

When the Romans arrived, they did not discover an empty landscape. They entered one already known — walked, worked and watched.

Roman roads cut through North Wales with purpose, linking the region to Deva Victrix — Chester, still known in Welsh as Caer. From there, routes extended through settlements such as Caerwys, just a short distance from Maes Mynan, tying this place into a vast imperial network.

Stone roads, forts and boundaries remain visible long after the empire itself has faded. Yet even as legions marched and messages travelled, the wren continued its quiet life along hedgerows and woodland edges, unaltered by ambition or authority.

Empires impose order. Nature adapts.

The Roman presence added a layer to the story of this land — but it did not overwrite what came before. Beliefs shifted, languages evolved, yet the rhythms of the seasons endured.

Chapter V

Princes, Giants and the Measure of Power

Long after the Romans had gone, this land continued to matter.

Maes Mynan was not simply a place to pass through, but a place to govern from. In the medieval period, Welsh princes established a llys here — a royal court, both political and domestic — anchoring authority in the landscape itself. Power was exercised not from distant stone keeps alone, but from places that were lived in, walked, and understood.

The choice of Maes Mynan was no accident. From here, the surrounding lands could be seen, known and protected. Hills, valleys and routes formed part of a living map — one shaped by familiarity rather than abstraction.

And yet, even these princes inherited stories older than themselves.

Local folklore speaks of Mynan the Giant, a figure said to have walked these lands long before courts or borders existed. His presence looms large in imagination — a being of immense size, striding across hills and valleys, shaping the land through sheer scale and strength.

Placed alongside the wren, the contrast could not be greater.

Where the giant dominates through size, the wren survives through wit. Where princes ruled through lineage and land, the wren claimed its place through cleverness — earning its title as King of Birds not by force, but by insight. In old stories, it outthought the eagle itself, rising higher by knowing when to move rather than how hard to push.

Here at Maes Mynan, those stories sit side by side: giants and princes, courts and folklore, strength and subtlety. Together, they suggest a deeper truth — that power is not measured only by scale, but by awareness, adaptability and understanding of place.

The wren does not challenge the giant.

It simply outlasts him.

Chapter VI

Gŵyl San Steffan and the Turning of the Year

In Wales, St. Stephen’s Day, is known as Gŵyl San Steffan.

It is celebrated each year on 26 December — the day that follows Christmas, when the land feels quieter and the season turns inward.

This has always been a day of pause rather than display. The feasting has passed, the light is low, and the year itself seems to hold its breath. Long before calendars fixed its place and the day became representative of a day of sport, this day was a moment sat close to the winter solstice, a threshold which see light emerge from the darker days.

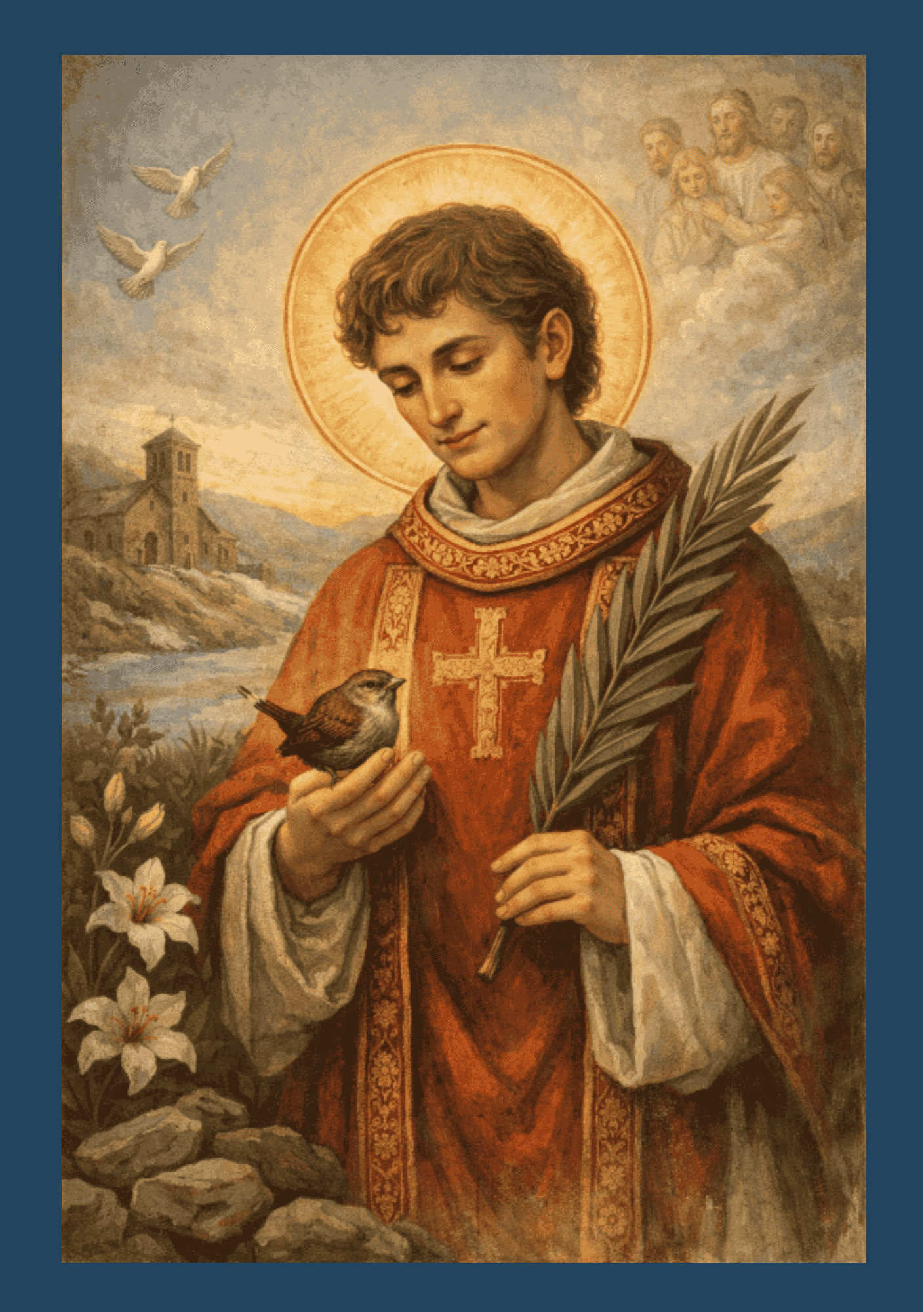

St. Stephen, remembered as the first Christian martyr, came to embody humility, sacrifice and compassion. And it is through an old Christmas carol that his story remains closely tied to the season itself.

In Good King Wenceslas, the Feast of Stephen is set firmly in midwinter:

“Good King Wenceslas looked out

On the Feast of Stephen,

When the snow lay round about,

Deep and crisp and even.”

The image is not one of celebration, but of responsibility. A ruler looks out across a frozen landscape and chooses kindness over comfort. Charity over ease. Action over ceremony.

It is a story of leadership measured not by power, but by care — a theme that resonates strongly with older traditions of this time of year.

As Christianity spread across Wales, it did not erase earlier seasonal beliefs, but wove them into new meaning. Gŵyl San Steffan became a day shaped by both faith and older rhythms — a moment of reflection at the turning of the year.

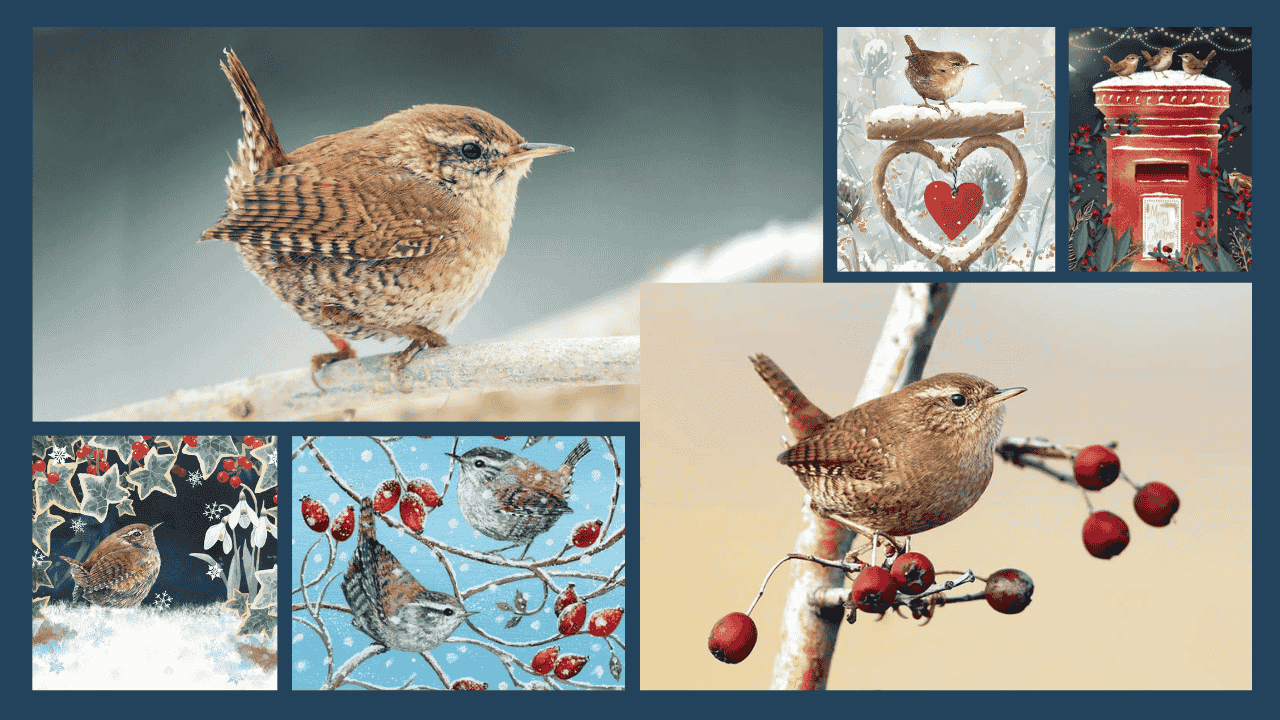

Here, the wren enters once more.

In folklore, the wren became linked to St. Stephen’s story, because in legend, it was said it betrayed him with its song. Traditions grew around the Wren Hunt ritual on 26 December, across parts of Wales and other Celtic regions. Although Christianity linked the ritual to St. Stephen’s Day, it is believed to be an older tradition linked to the passing of the shortest day. Over time, the ritual shifted from literal to symbolic, marking the close of the old year and the uncertain beginning of the new.

The wren, small and alert, stands again at the threshold of a new year.

Neither wholly blamed nor fully celebrated, it becomes a messenger of transition — carrying the weight of endings and the promise of renewal. Like the Feast of Stephen itself, the wren belongs to the quiet after Christmas: a time for humility, awareness, and noticing what remains when the noise has passed.

On Gŵyl San Steffan, the year does not announce its turning. It simply begins quietly – softly.

Chapter VII

The Park in Midwinter

At Maes Mynan Park, winter asks little of the land and much of our attention.

Winter at Maes Mynan carries the same quality as the quiet after Christmas.

The celebrations have passed, the calendar has moved on, yet something lingers in the air — a stillness that invites reflection rather than action. This is not a season of absence, but of attention, where the land asks little and offers much to those willing to slow down.

Paths crunch softly underfoot. The air feels sharper, clearer. The lakes reflect a quieter sky. This is a season that rewards those willing to slow down and notice.

Our Holiday Parks are designed with this relationship in mind — not to dominate the landscape, but to sit within it. Parkland and woodland are not decorative features here; they are living ecosystems, offering space, shelter and connection.

Holiday homeownership in a place like this is not about escaping the seasons, but about experiencing them fully — understanding that winter has its own richness, its own presence, its own life.

And still, the wren moves among the shrubs.

Chapter VIII

Acknowledging Small Things

As the year turns, there is no announcement. No clear dividing line. Just a gradual shift — in light, in temperature, in feeling.

This is the moment that follows Christmas.

The same moment marked by Gŵyl San Steffan, when the celebrations fall away and what remains is character, humility, and care. A time not for looking inward alone, but for looking out across the land, attentive to what endures.

The wren understands this instinctively. Small, alert, unassuming. It survives winter not by resisting it, but by living carefully within it, noticing shelter, conserving energy, and knowing when to move.

So if you find yourself walking Maes Mynan Park in the days after Christmas, or looking out across bare branches and quiet hedgerows, take a moment to listen. The ‘druid of all birds’, has a wonderful note to share. It’s not a grand statement or loud signal, but a reminder of the small things that last.

It’s a note that says the little wren is still here.

And, as on the Feast of Stephen, the year turns quietly, we can, with distance of time, allow the story to soften.

The wren, once blamed in legend, has endured every retelling — not through defence, but through presence. And as St. Stephen is remembered for his humility and forgiveness, he reminds us that he stands not as a figure of accusation, but of compassion.

Seen together, they speak less of betrayal and more of resilience. Of life continuing through change. Of meaning reshaped rather than lost.

On Gŵyl San Steffan, as the year begins its quiet turn, the wren still moves through hedgerows and winter shrubs, indifferent to the historic stories placed upon it. Nature carries on — patient, forgiving, enduring.

And perhaps that is the message that remains: that renewal does not come through blame, but through understanding; not through power, but through persistence.

The little wren is still here. And the year, like the land itself, begins again.

acornleisure.com – info@nullacornleisure.com – 01352 720808.

Holiday Homes For Sale – Holiday Home Ownership at its best in North Wales